The story of triptans: from historical hallucinogens to myth-busting migraine relievers

Pharmaceutical roots is a content series from LGC Mikromol investigating and outlining the natural origins of pharmaceutical substances, and offering a deeper dive into their uses, risks, and mechanisms of action.

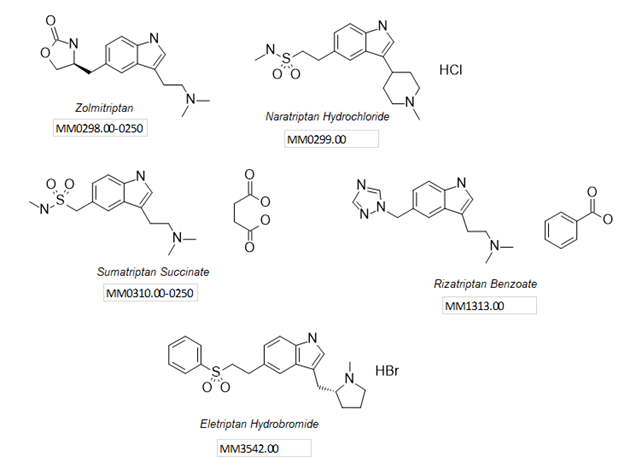

We supply a number of API and impurity products for triptans. For more information, please scroll to the bottom of this article.

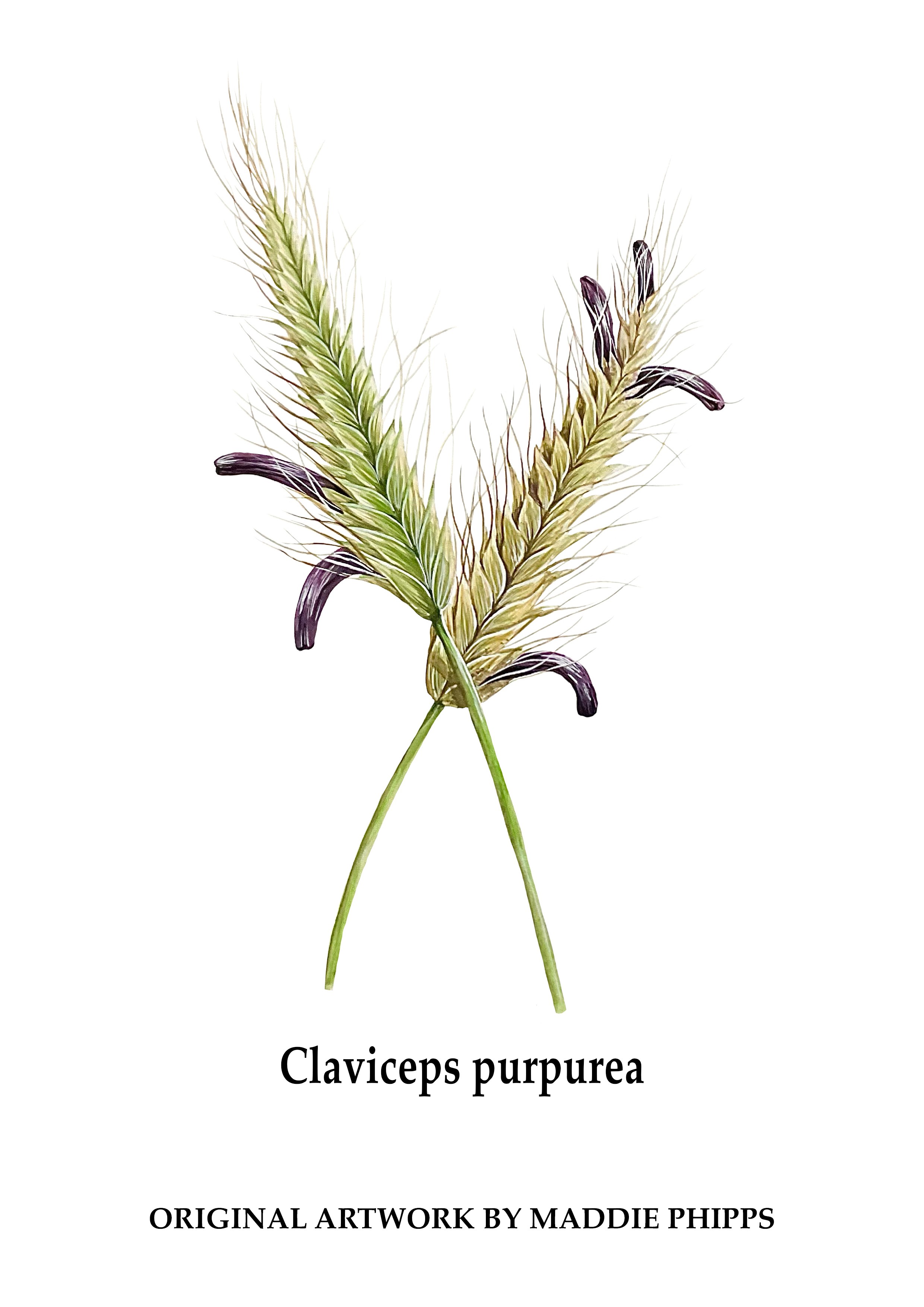

It took more than 2,500 years, but an ignoble fungus called the rye ergot finally had its day in 1993, when the antimigraine drug sumatriptan first went on sale. Over the millennia, rye ergot had acquired an appalling reputation: an Assyrian tablet from 600BC first alluding to the “noxious pustule on the ear of grain” that caused thousands upon thousands of people to develop gangrene or suffer wild hallucinations. But the once-dreaded poison lurking in your supper bowl “changed its role over the centuries to become a rich treasure house of valuable pharmaceuticals”. Eventually, midwives and doctors began to appreciate that the fungus – also known as claviceps purpurea - could be used to relieve suffering as well as inflict it. Thus began a long scientific process that culminated in the synthesis of triptans, the first effective treatment for the ancient and widespread curse of migraine. What’s more, these pharmacological descendants of the unloved ergot also helped slay some enduring sexist tropes about migraine and women – proving the condition had a neurological cause rather than being rooted in so-called feminine ‘neuroses’.

History

In medieval times, the condition known as St Anthony’s Fire was a common but distressing occurrence. A person who ate rye contaminated with claviceps purpurea could experience two main symptoms of the disease: hallucinations, or gangrene in the feet that made them feel they were “being bitten by unseen teeth”.

Today, we also know that rye ergot is an alkaloid that can bind serotonin receptors and overstimulate them, causing hallucinations (the fungus is also the source of lysergic acid, the active component of psychedelic LSD). The gangrenous symptoms of St Anthony’s Fire were also caused by the stimulation of serotonin receptors on blood vessels, causing constriction so severe that flesh would become necrotic. In the medieval period, however, the best that sufferers could do was go on a pilgrimage in the hope of easing their suffering – which at least might take them away from the contaminated rye!

At some point in the story, carers discovered that there were benefits to the way that claviceps purpurea constricted blood vessels. By the 16th century midwives were using it as a means for speeding up childbirth, and pastes of rye ergot were later employed to stop uterine bleedings after labour. By 1918, Swiss biochemist Arthur Stoll “isolated ergotamine, the first chemically pure ergot alkaloid, which found widespread therapeutic use in obstetrics and internal medicine”. Studies on the rye ergot also eventually led to the discovery of serotonin in the 1940s (the word ‘serotonin’ means “substance from the blood that increases the tone of the blood vessels”). And, by the 1970s, the search for a drug that could mimic ergotamine’s benefits without its side effects had begun. When sumatriptan was first marketed in the USA in 1993, it was regarded as “a revolution for people with migraine. Nothing before had been SO effective to treat migraine attacks.”

Mechanism of action

Triptans provide migraine relief by binding to 5-HT1 receptors in the brain. There, they act to constrict extracerebral blood vessels within the cranial vasculature, inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators from sensory nerve endings in the trigeminal system, as well as nociceptive transmission.

Triptans all bind with high affinity to three serotonin receptor subtypes: the 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1F. They have strong agonist activity at the 5-HT1B receptor (which mediates cranial vessel constriction), and at the 5-HT1D receptor (which leads to inhibition of the release of sensory neuropeptides from perivascular trigeminal afferents). 5-HT1B mRNA is densely localised within the smooth muscle and - to a lesser extent - in the endothelium of cerebral blood vessels. This vascular distribution of 5-HT1B receptor has been shown to mediate the vasoconstrictive properties of triptans and is responsible for potential cardiac adverse events, significantly limiting its use in high cardiovascular risk populations. 5-HT1B is also expressed in the nociceptive afferents conducting nociceptive information to the spinal cord/trigeminal ganglia, and its activation in this location was found to reduce the release of facilitatory neurotransmitters responsible for the stimulation of central nociceptive circuits.

Stopping migraines, challenging sexism

Globally, migraines cause huge damage to health and the economy, and are the second-largest contributor to years lived with disability. They affect one in five women – but only one in 15 men - and cause an estimated 25 million sick days in the UK alone. Yet migraines are also one of the world’s most under-researched diseases, receiving 13 times less research funding than asthma and 50 times less than diabetes. One BBC article claims that: “Given the prevalence of migraines among women, this apparent neglect could be a result of how physicians tend to underrate pain in female patients.” Moreover, “It may also reflect the historic – and similarly gendered – associations between migraines and mental illness.” Before the invention of triptans, “migraine was still seen as a neurosis” and women experiencing acute headaches “were often ridiculed and seen as hysterical”, or pitied for having “delicate nervous systems”. Sumatriptan’s other great achievement, therefore, was that it “challenged this vision” of migraine as a predominantly feminine mental disorder - simply because “the relief was very quick and suggested a biological, neurological cause more than a psychiatric one.”

To support your analysis and help ensure the accuracy of quality processes, we supply a range of API and impurity (intermediate and degradation) products for seven triptan API families, with five 17034-accredited APIs (see below) including sumatriptan succinate and zolmitriptan, plus a new impurity standard for almotriptan maleate.

Discover all our LGC neurology materials here, and get in touch if you have any questions about how we can support your work. You can also explore our full Mikromol range of pharmaceutical reference standards:

|